In the past, if an illustrator asked what they needed for a

successful portfolio, he or she would have been told, “every portfolio must contain the three h’s -- head, hands,

and heart”. Head referring to concepts, hands referring to skills, and heart

referring to desire. These days, a portfolio is expected to contain much more

than that. It not only must demonstrate what you have done in your past, but must also predict what you might achieve in your

future. A portfolio must be able to weather all situations. Below are a number of tasks a portfolio must now do.

|

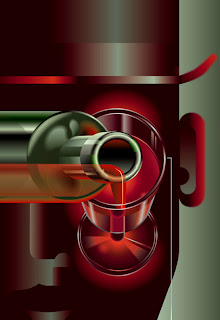

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

Do Establish the Purpose for

Your Portfolio

Is it to obtain full-time employment, a freelance commission,

a teaching position, a gallery exhibition, etc?

First and foremost, it is important to know what you want

your portfolio to do for you. The purpose for a portfolio is the single largest

determining factor in how the portfolio will look and function. A portfolio

constructed for interviewing for a full-time position will have to function

differently than one that is meant to attract freelance work, or is for some

other purpose.

Do Know Your Audience

Are they a creative person such as an artist or designer; or

are they a non-creative person such as an editor, writer, marketing person, or

business owner?

Just as advertisers, marketers, product developers, and

manufacturers exhaustively research their audience to get to know their

customers, you should do likewise. Differing audiences will require varying forms

of communication and possibly even different language sets depending of their

knowledge of what it is you do. These factors will affect the form and content

of your portfolio presentation.

Do Know How to Reach Your Audience

What are their job responsibilities, and the type of business

they work for? Do they have a preferred method of contact? Can you contact them

through a referral?

It’s important to know if you are dealing directly with

someone who has the power to make a decision, or someone who can only relay

information within a company. It’s also essential to know if the business they

are in can hire your services directly, or whether you should be in contact

with another outsourced company or division. For instance, to work for Pepsi,

you will have to deal with an outside firm.

Do Know What Will Attract Your Audience

Have you seen the work they do and what their company does?

Are you familiar with the type of work they typically commission? Do you know

who their customers are?

Every company has a set of criteria that provide guidance

for the type of work that they do. The criterion also sets the personality and

style of their business. For some companies like children’s book publishers for instance, it

is obvious, but for design firms and advertising agencies it may take some research on your part to know

what demographic they specialize in and who their clients are. The work shown

in a portfolio should be chosen accordingly.

Do Select the Appropriate Portfolio Media

Will you need a physical hard copy portfolio, a virtual

digital portfolio, a website portfolio, a disposable portfolio, etc.?

Pertaining to marketing, aspects of presentation and a portfolio’s function, you should know whether you are seeking a job or commissions locally

or nationally. Whether you can get by with a digital or web-based presentation,

or whether you will have to appear for an interview in person, and with whom.

Do Select the Best Format

Does the portfolio need to be small or large, physically

shipped or emailed, horizontally formatted or vertical, individual panels or a

bound presentation?

If most of your work is vertical, arrange your portfolio so

the spine is vertical. If the work is predominantly horizontal use the cover or

case to indicate that orientation since there are relatively few commercial portfolios made

with a horizontally oriented spine. Choose a format that will easily allow you

to reconfigure your portfolio quickly if you will frequently need to do so.

Do Determine the Number of Illustrations

Should you show many illustrations or a select few? If you

have a series, should you show all of its pieces? How similar in style, format,

or appearance should the work be?

Most illustrators show more pieces than they should, and

most reviewers tend to experience visual fatigue and attention deficit somewhere

between 20 and 25 pieces. The main goal is to leave a lasting impression with

the work. Work that is repetitious in composition, color scheme, point of view,

and content tends to blend together. Work that presents a variation of aspects

tends to be more memorable.

Do Choose the Right Illustration Content

Should you include only published work? Should published

work be presented as tear sheets? Should it be full-page illustrations, or

should you also include spot illustrations, icons, etc? Should you include

black and white work? Should you show all finished work, or add in concept

sketches?

Illustrators who have a few years of experience are expected

to show published work. Illustrators just starting out are not subjected to the

same expectation. The content of a portfolio should be a combination of “absolute

best work” and work that relates to the opportunity at hand. If black and white

or other forms of work are a part of the repertoire of the reviewer than they

should be in the portfolio.

Do Seek Opinions on Content

Are you the best judge of your own work? Have you gotten

positive feedback about specific pieces? Do you know someone who can lend you

an opinion?

One of the most difficult tasks in creating a portfolio is

selecting the work. Even illustrators with years of experience need help when

it comes to curating their work. Artists often develop a bias towards certain

pieces. It may have to do with the great amount of effort it took, or

successfully pleasing a difficult client, or some other prejudice. These

situational conditions should be overruled by quality.

Do Provide a Context For The Work

Have you provided relevant titles or client information for

the illustrations? Can you provide a sentence to summarize an assignment or to explain the

purpose for the work?

Any information that explains to a viewer what they

are looking at can be as valuable as the work itself. In a portfolio, all

images appear to be very similar in proportion whether they were produced for a

3’ x 4’ poster, or a small format magazine; or whether they were done for a nephew,

or a multinational company. Having the work placed in it’s proper context is

important for a reviewer.

Do Match the Context to Your CV

Are you showing illustration examples that match the

employers and clients you list on your resume? Do the examples demonstrate the skills

you have listed? Does the work reflect either your job objective or your

experience summary?

It is very easy for a resume and a portfolio to present a

split personality. A common example, although it is not necessary, is to list

freelance projects on the resume. Reviewers will want to see the pieces that

correspond to the listings. And, should the work shown in the portfolio diverge from actual past

experience, it can be easily addressed with a career objective statement on the resume. Both

credentials should be mutually supportive.

Do Design Your Portfolio

Can your portfolio case or binder be differentiated from

other portfolios when it is closed? Does the interior layout of your portfolio compliment

your work or compete with it? Is the layout uniquely identifiable? Does the

page size and scale of images show off the level of detail in your work? Do

images sit opposite one and other on page spreads if you are using a bound

portfolio? Does your portfolio shift from a horizontal orientation to a

vertical one several times?

All aspects of your portfolio presentation should be

customized to leave an identifiable impression on a reviewer, from the

materials used, to the layout, color scheme, and application of typography.

Reviewers sometimes look at a dozen or more portfolios, which equates to viewing 200 to

250 images within a single sitting that lasts less than one hour. So in addition to the work, a portfolio’s

design must also form a memorable impression.

Do Work on the Order of the Work

Do adjacent illustrations compliment one and other? Is there

a natural progression of work? Does the order of the work support a

presentation narrative? Does the arrangement of works at any point cause a

reviewer to make a “this is better than that” judgment about two pieces? Is the

arrangement the visual equivalent to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony?

Organizing the sequence of work in a portfolio is a subject

unto itself, and although there are unlimited possibilities, there are some

strategies that work better than others in certain situation. The work itself

must be high in quality to provide the best source for a portfolio, regardless

of any organizational tactics. Some of the most common approaches will be

covered in a future posting.

Do Support the Work With Branding

Do you have a logo or specific type treatment you can apply

to your materials? Do you have a specific color scheme? Does your portfolio

coordinate with your resume, mailers, business card, website, etc.?

Branding goes hand in hand with portfolio design and

function. Branding not only serves to promote recognition, but it reinforces

memorability and reveals the rank of a professional. Branding, once

established, provides solutions for many design and promotional problems that

arise when preparing marketing materials like the appearance of the resume,

cover letter, mailers, stationery, home page design, etc.