When it comes to solving problems and

thinking up ideas, there has been a long running debate as to whether these

skills must be an intrinsic, instinctual, “creative” talent within a person; or

whether creative problem solving be achieved as a learned intellectual ability.

For professional visual problem solving illustrators, designers, or artists it

is a bit of both. Either way, it is a necessary requirement for anyone

considering a career as a creative visual artist.

Professional illustrators usually don’t have

the time or luxury to wait for that lightening stroke of inspiration to

materialize a brilliant idea. Most of us have to work at it, that’s what makes

illustration a profession. And just about every illustrator I know has a

different way of solving a problem to complete a job. I’ve heard of many

methods for getting the creative juices flowing, from taking a shower, to

running in the park, to staying up straight for 40 hours, to eating pizza after

midnight, to prayer, and to even asking pets for advice, seriously. All this in

the hopes of getting a great idea.

When asked how he always had great ideas for

illustrations, Seymour Chwast replied, “ I don’t always get great ideas, I just

never show anyone the bad ones.” When animation director, Chuck Jones, was

asked the same question, he replied with one word, “fear”. The fact of the

matter is we all get ideas all the time about everything, and we do get ideas for the illustration

projects we are commissioned. The problem occurs when it comes to the quality

of these ideas we get. And, as it was for Chuck Jones, the “fear” of not being

able to come up with an idea or of getting a dreaded “mental block”.

The solution is to apply a working method to

solve the problem posed by the assignment and client. Understanding the process

of thought that is involved with solving a visual problem can be very useful

for challenging assignments.

Whether illustrators are aware off it or not,

they instinctively apply many of the following stages of problem solving in the

process of working on an assignment. The following is a process for generating ideas and

avoiding mental blocks.

|

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

The Assignment (The Problem Stage)

Client Input

Usually a description with a collection of

facts and information describing the assignment and the desired outcome. The

assignment will probably be related in terms that are familiar to the client.

Most likely the information will be in non-art terms and may involve marketing

information and technical specifications. This is a good thing, as clients

generally don't have knowledge of visual terminology. You may receive the

assignment directly from the client or from an intermediary such as an art director or an account

executive. Either way it won't be from an illustrator.

Reinterpretation of Client Input

To prepare for the process of “creative

construction” it's necessary to translate the client's description into

artistic terms that you can work with, i.e., a personal reinterpretation that

applies to pictorial terms and ways of working to allow you to act on the

assignment task and content. Reinterpretation will help identify any missing

information the client overlooked in assigning you the job, in which case you

can ask for further explanation, additional facts, or clarification.

|

| © Don Arday. |

Creative Construction (The Thought Stage)

Open Brainstorming

When you begin to think about a problem, it

is important to record any and all ideas, thoughts associations, experiences,

first impressions, etc. about the subject. The record of this activity may take

the form of visual sketches, written words or short sentences. These will

become the building blocks of further ideas. And it is absolutely critical you

remain non-judgmental about the ideas you come up with, good, bad, ugly or even

silly ones. Don’t disregard any ideas. Know that brainstorming is a very

personal activity. At this stage the ideas generated are for you and you alone,

and sometimes thoughts that are seemingly unusable may lead to ideas that are.

Also, it is not sufficient to simply have the thoughts; they must be put on

paper in one form or another. This process can be completed in a short period

of time or it can take much longer.

Focused Brainstorming

This thought session involves searching for

ideas independent of the first thought session, trying to expand the number of

ideas to add to the material you already thought of to produce final sketches

to present. The main difference is that this time you should relate all of your

ideas to the assignment. Try to improve on your original set of ideas. Once

again, try to avoid metal blocks by being to judgmental about your ideas. It's often our own judgmental expectations that stand in the way of our creative thinking.

|

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

Research (The Education Stage)

Subject Research

One of the most interesting things about

being an illustrator is all the things we learn about various subjects, in order

to produce illustrations. You must familiarize yourself with the subject of

your design problem. This will aid in eliminating stereotypical ideas you may

have concerning the subject such as previously publicized phrases or visuals.

At all times during this process you should be adding to your cache of ideas.

Research is an important part of any problem solving process and should be part

of your creative fee. Although I prefer to brainstorm ideas prior to

researching facts, some illustrators prefer to proceed directly to the research

stages before attempting any brainstorming.

Media Research

These days it is especially important to

consider the media requirements of the assignment. You must become aware of the

specific production processes, materials, and limitations that will influence

the completion of your illustration. Budget also becomes an extremely important

consideration here. This research will help you make visual and production

decisions that will influence the look of your illustration. For example, a

small, illustrated logo or icon will work better with a high key contrasting

color scheme. Dark colors and subtle tones should be reserved for larger

display formats. Also, an illustration that will appear on the web may require

a different amount of detail and production resolution, than one that will be

printed with a 200 line-per-inch screen on a sheet-fed offset press.

|

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

Evaluation (The Decision Stage)

Idea Review

Now it’s time to be judgmental. Idea review

is the time to look for some personal benefit that might result from your

choice of ideas. This is the stage where you assess all of your thumbnails and

other recorded material and select those ideas you feel the most positively

about. You can set your own personal criteria to judge the quality of the

ideas, like which ones would enhance your portfolio, which ones will best suit

your style, or make a great composition. Or you can place classifications

on the ideas such as practical, attractive, unique, client suggested, etc.

Criteria Review

Consider the criteria given by the client. Re-evaluate

your materials and relate them to the requirements of the problem reinterpretation.

Search for unique qualities inherent in your ideas to bring attention to your

client and even yourself, or ideas that may lend themselves to added benefits,

such as a concept that is versatile or marketable. Criteria review is when you

choose ideas that will benefit the client and cross-reference them with

personally beneficial ones to choose which idea(s) to present. The idea(s) that

will motivate you the strongest and you will be most excited to produce--a win,

win situation.

|

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

Development (The Proposal Stage)

Idea Implementation

Now that you know exactly how you want to

proceed with the assignment, obtain the specific visual references necessary to

visualize your ideas. Begin the final sketch stage, all the while ironing out compositional

problems. This is also the point where you should consider the actual working

methods needed to produce the finished illustration that will be dictated by

the sketch. It is advisable to plan out a logical schedule of action when the sketch is

approved to save on time and any production answer questions the client may have.

Support Rhetoric

Sketches don’t sell themselves these days so

it’s very important to provide some verbal support for your idea, whether it is

spoken or written. Even though you may have provided verbal support, be

prepared to justify all decisions concerning the idea and your sketch. It is

not enough to be able to intuitively produce a pleasing idea. You must sell

your idea clearly. The idea, in turn, will be sold again by whom ever you sell

it to, especially if your client must present it to their superior or a

constituent. See “10 Steps To Presenting Illustration Ideas Successfully”, posted on 12/11/12, theinformedillustrator.com.

|

| © 2013 Don Arday. |

Production (The Finish Stage)

Completion

This is the stage where approved ideas are turned

into finished illustrations and prepared for delivery and commercial

production, most likely, as a digitized file. All the formal visual and media

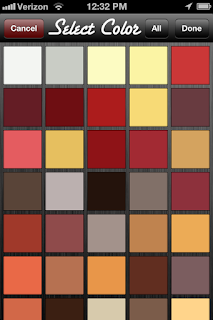

considerations are finalized at this stage; media, format, size, composition, color

scheme, visual elements, digital resolution, file preparation and archiving, etc.

Final Review

You are finally finished. But are you? This is perhaps the most

important stage prior to the release of the finished illustration, and the one

illustrators most regret not doing. Take some time to look the final

illustration over very carefully and make sure you are completely comfortable

with all the decisions you’ve made. I call it the 5-Minute Rule, take 5-minutes

to look over the work. If something “bothers” you, then correct it. It’s the

last chance.